The Underlying Option Expiration

By Terry Rossio

It can be a bit painful to see a film head into production, based on a book that you’ve adapted, but it’s not the adaptation you’ve done.

I’ve had that happen three times.

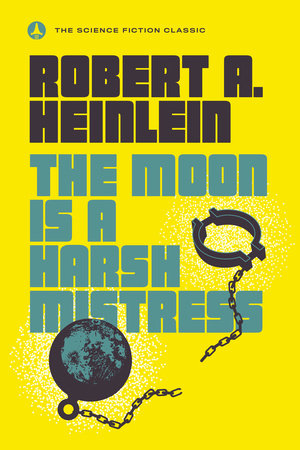

Neil Gaiman’s wonderful Sandman graphic novel series. Edgar Rice Burroughs’ A Princess of Mars, which eventually hit theaters as John Carter. And the most interesting case, Robert Heinlein’s The Moon is a Harsh Mistress.

(Sandman and Mistress are reportedly in pre-production as of this writing.)

Typically, what happens is the studio options a book, and the screenwriter is hired to write the screen adaptation. Because the studio has not purchased the book rights, the screenplay is only viable, practically speaking, during the option period. You’ve got a year or two where they have to proceed to production, or their option expires and the film rights revert to the author. (Essentially, the studio doesn’t want to spend the full price to own the film rights until they know whether the project will be produced and distributed.)

Once the option expires, the screenplay draft becomes a ‘lame duck’ draft, of value to no one, because the underlying rights are no longer owned. If someone new comes along, and options the underlying rights again, they wouldn’t own the rights to the screenplay. The script becomes stranded, without a home.

The Moon is a Harsh Mistress is an interesting case, on two counts.

After the option expired at DreamWorks, the book rights were subsequently picked up by another company. Now, you would think it might be a simple matter to contact that company and say, “By the way, there already exists an adaptation of this work, over at DreamWorks, and I bet they’d be willing to sell it to you for a song, since they no longer own the film rights, so why don’t you give it a read?” If they liked the script, they’d get a ready-to-go project at a bargain rate; if they don’t like the script, no harm no foul, they could always proceed with their own adaptation.

Makes sense, right?

And it would be a great deal for the screenwriter, who gets another chance at a payoff for all the time risk invested in the project.

But it can’t happen.

Not that it didn’t happen; the way the system is set up, it can’t happen.

We contacted the new studio, and made the proposal. Their answer was the common answer — due to potential legal issues, they couldn’t afford to even look at the existing draft. Problem being, if they read the screenplay, but didn’t buy it, they’d be setting themselves up for a plagiarism lawsuit. Their eventual adaptation might use similar solutions, similar selected elements, or through parallel development, similar embellishments. Or they would have to dodge every new idea in the adaptation they read, even if they might have come up with the same ideas later, and that would be a nightmare.

So lame duck drafts on projects rarely even get considered. (And where’s the fun in that, anyway? Typically filmmakers get excited about projects because they want to do their own version of a project, not execute someone else’s version.)

The second way Mistress is an interesting case goes back to when the adaptation was written. The screenplay was completed about a month prior to the rights renewal date, and to be honest, we nailed it. The source material is of course fantastic, one of the top ten science fiction novels of all time, and the draft we turned in would have made an amazing film. The renewal date came and went, with no word from the studio, but a few days later we got a phone call. “We’re going to let the rights expire,” said the executive. “Did you not like the script?” we asked. “I’ll be honest with you,” said the executive, “We’ve been really busy. I’m sure the screenplay is fantastic, you guys always do good work. But we just didn’t have time to read it.”

While this sounds insane from a business perspective — why option the book rights at all, on such a high profile project, or hire screenwriters to do an adaptation — it makes perfect sense from a time risk perspective. If you’re an executive, and you know the project doesn’t fit your production schedule, why expend the time risk to even read the screenplay?

Copyright 2016 Terry Rossio

<http://www.wordplayer.com>

Link to article: http://wordplayer.com/columns/wp55.Time.Risk.html#Heinlein